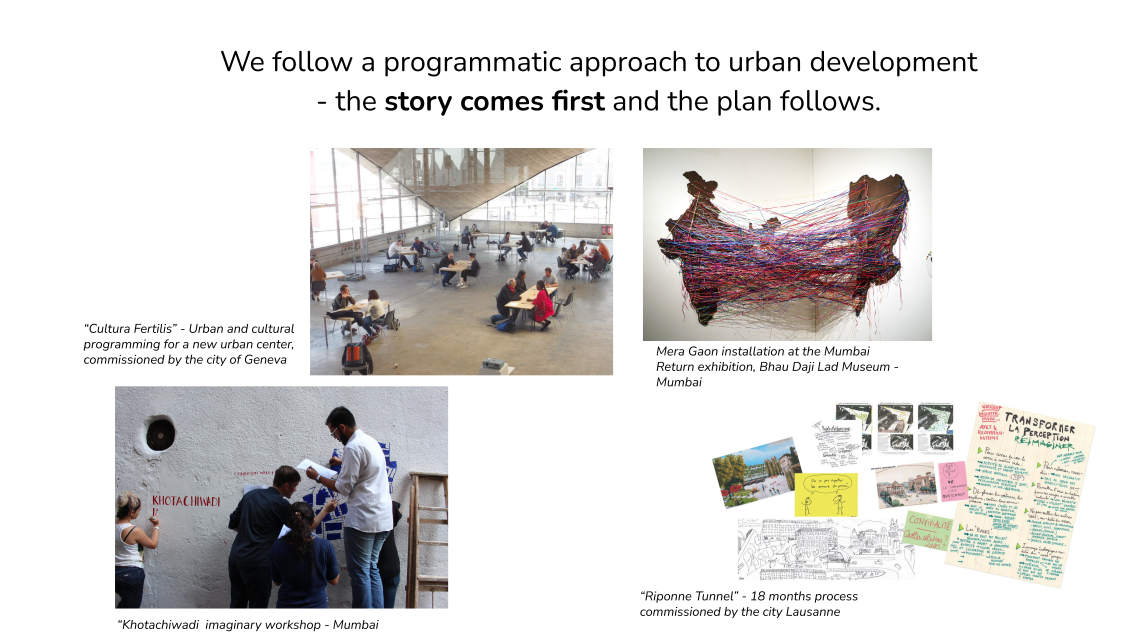

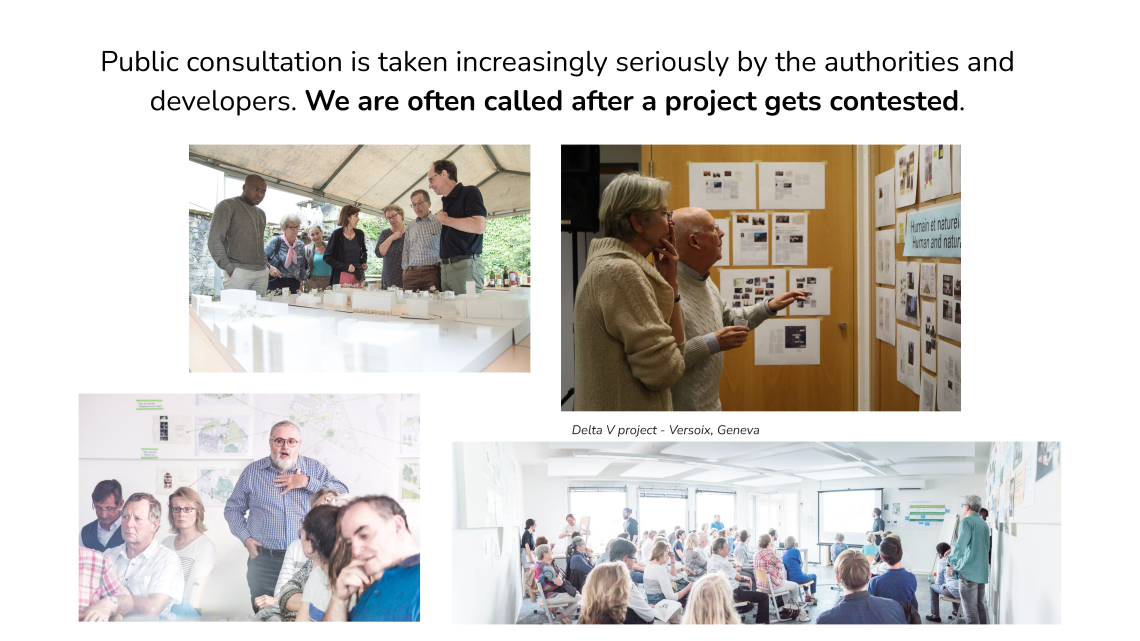

Swiss authorities and real estate developers take public consultation increasingly seriously. We are often called after a project gets contested or rejected by vote. Sometimes we work on projects from their inception, which is of course the way it should be done.

When we come to a project after a first version was rejected by a referendum, the first question we ask to people who opposed the project is always: “are you against any form of development or would you be open to another plan?” The vast majority of people are not opposed to development as a matter of principle. They just want something that makes sense to them and adds to their quality of life.

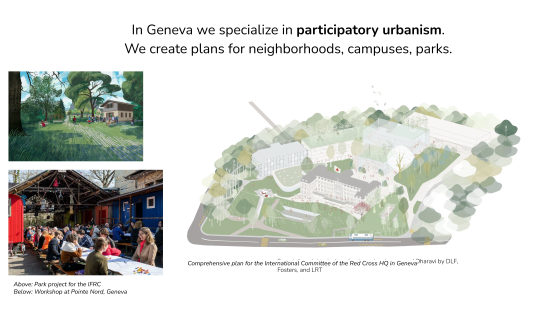

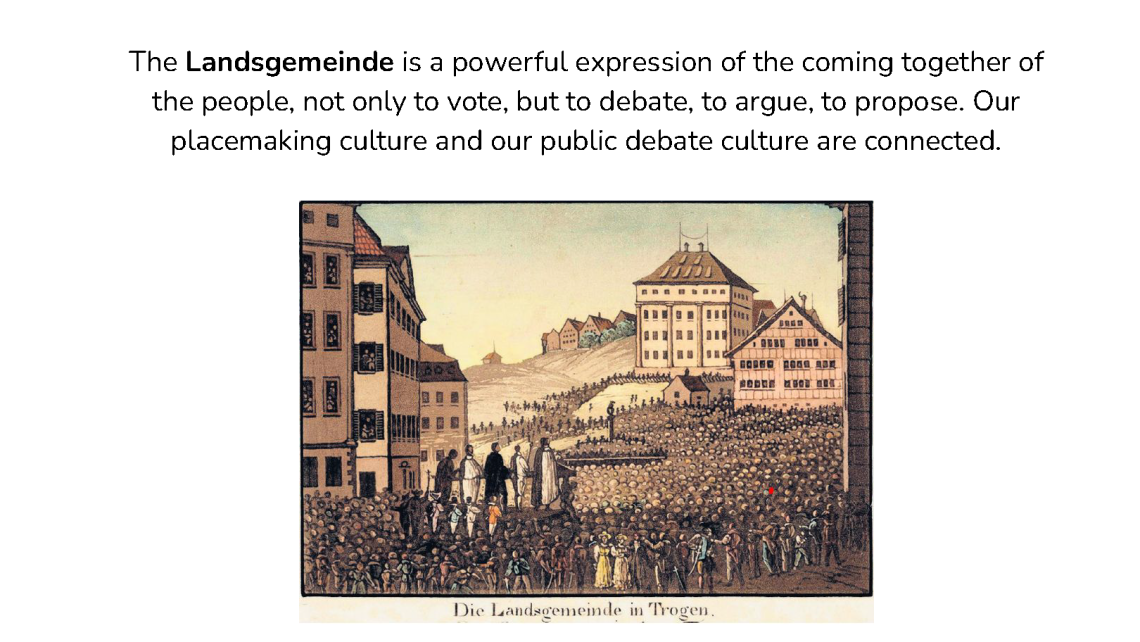

While modern urban planning has turned urban development into a technocratic affair, led by experts, investors and politicians, it wasn’t always the case. Participation in the production of our habitat is nothing new. In fact it is something that has always existed in Switzerland and in every part of the world. Before we created institutions and corporations that have taken on the role of producing habitat for us, people were actively involved in the construction of their houses, in the edification of monuments, and even in the provision of infrastructure. People have a natural propensity of shaping their milieu. When this impulse is denied, it creates a deep sense of frustration and powerlessness.

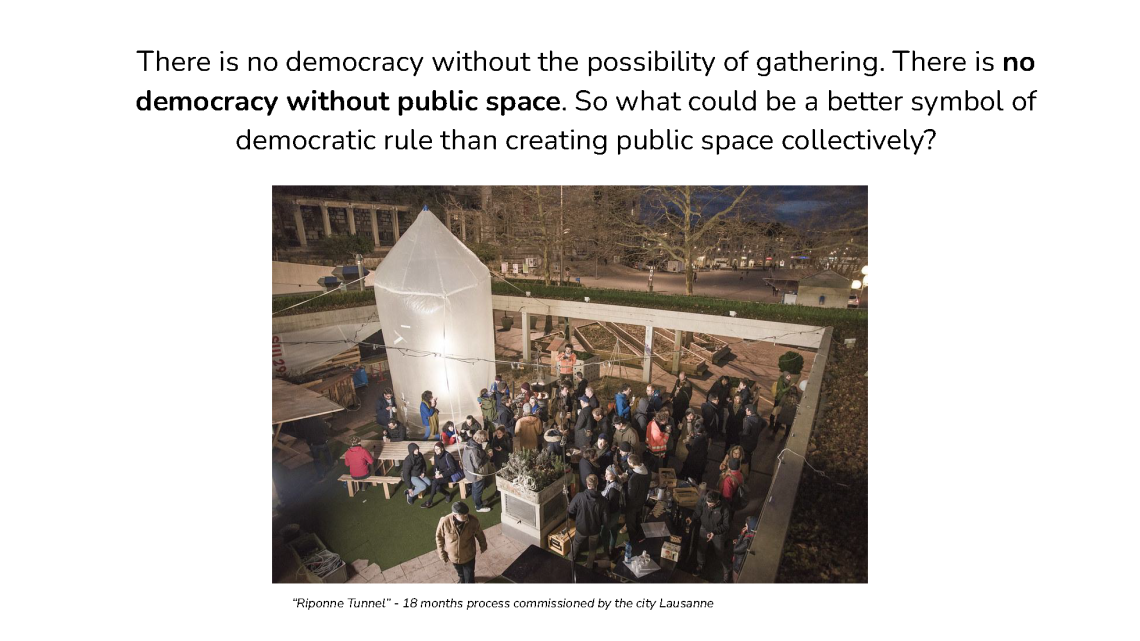

We must recognize our collective strength and the resources we have access to: every locality has human capital (skills), existing constructions, and a rich natural ecosystem (even the most urbanized places). We must trust each other and ourselves and reclaim our collective capacity to shape our habitat.

This requires communication between people, but also with the authorities. As Melvin Webber stated is "no linguistic accident that “community” and “communication” share the Latin root communis, “in common.”" It is our ability to communicate that provides us with meaning and a shared sense of purpose. We must evolve our institutions and our ways of functioning so they become a little more open to whatever seems to be out of the box.

Collective, cooperative and participatory construction of habitat is part of the human experience. It is about dealing with each other as much as dealing with our environment. It is still very much alive in Swiss culture, just as it is alive in Indian, Japanese and every other culture in different forms. These processes are social and political in nature.